2020 Midwinter Armizare Open

Saturday, January 25, 2020 at 10 AM – 7:30 PM

Broadway Armory Park

5917 N Broadway St, Chicago, Illinois 60660

5917 N Broadway St, Chicago, Illinois 60660

Tournament Rules

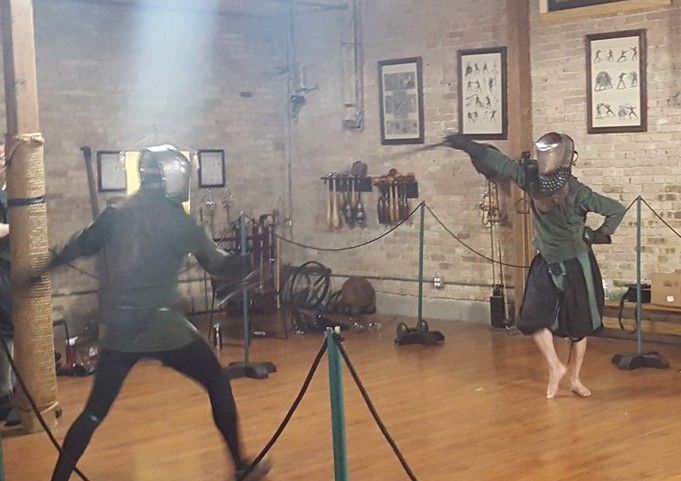

The Midwinter Armizare Open is a public display of skill with one and two-handed swords in a relatively rules-light format meant to emphasize the tactical priorities of fighting with sharp weapons in lethal combat. Midwinter Armizare Open 2020

TOURNAMENT ONE: LONGSWORD

Combatants will be divided into pools, fought under the below conditions, with an award to the overall victor. Combatants may also carry a dagger on their belt and switch to it when coming to grips.

TOURNAMENT TWO: SINGLE-HANDED SWORD

Due to the diversity of single-handed sword styles (and scarcity of focused exponents of the same), this will be a mixed-weapon tournament with the following, permissible weapons:

- Medieval arming-sword;

- Messer;

- Side-sword;

- Rapier (max blade length 45″);

Note: Sabers, backswords, broadswords, smallswords, etc are not permitted. (We love them, too, but we’re keeping this to fencing styles c. 1600 and earlier.)

TOURNAMENT THREE: PAIRED WEAPONS

The following weapon combinations are permissible:

Armingsword, sidesword or rapier, accompanied by:

- Dagger

- Buckler

- Rotella

FINAL ROUND: THE WINTER KING

As a culmination of the event, the victors of the three tournaments shall fight a mixed-weapons bout using the previously denoted scoring conventions, with the victor to be declared the winner of the overall tournament.

HOW IT WORKS

CONVENTIONS OF COMBAT

With the Sword

- Each bout is fought to a total of five landed blows;

- The entire body is a target;

- For our purposes a “blow” constitutes any “fight-ending action”:

- a solid cut with the edge, thrust, disarm or throw;

- a pommel strike to the center of the face;

- a thrust to the center-of-mass with the dagger.

- Incidental blows, light touches, flicks or hits rather than cuts, punches and open-handed strikes that do not end in a throw or lock, etc will not be scored.

With the Dagger

- Combatant may carry a dagger on their belt in the longsword tournament, and switch to its use as they see fit.

- Daggers may only strike with the point.

- If a dagger hit is scored, combatants must, after the halt, switch back to their sword.

Grappling

- Grapples that end in a throw with party dominant will score a point.

- Grapples lasting more than 5 seconds or deemed to be dangerous will be halted by the judges;

- Grapples that go to the ground with no one dominant will be halted.

SCORING

Once a fight is concluded, the combatants will report their scores to the list-table. Fights are scored as follows:

- Overall Victor receives 2 pts;

- If the Victor was not struck he or she receives 1 pt additional;

- The person who scored the first blow receives 1 pt;

- If there were any double hits during the match, both parties lose 1 pt.

- Therefore, in any match a combatant could score between 4 and -1 points.

These rules are not meant to be “realistic”, simply to prioritize drawing first blood and avoiding being hit and, most especially double-hits. No matter how many double hits, for the sake of simplicity, only 1 pt is lost. However, additional double hits are not refought, so if you rack up too many double-hits, the victory in that match is going to go with who scored the first blow, and your overall score is going to go down!

ADVANCEMENT: INDIVIDUAL TOURNAMENTS

There are two ways to advance to the final round of four combatants – by Score or by Accolade.

Score

After the Pool Round ends, total scores for each will be totaled, and the combatant with the highest score from each pool will move to the finals. (If two or person tie, then the person with the highest total of first blood scores will advance. If there is still a tie, the combatant with the most “never hit” scores will advance.)

Accolade

The list will be “balanced” by adding a fourth combatant chosen by the other combatants. If the list is already balanced, the Advancement by Acclaim will not be needed.

FINAL ROUND

Once the Finalist are assembled, they shall fight with the prior scoring conventions in a simple single elimination tree. (NB: In the event of a small final list (four or less), the finals may be fought as a pool at the judge’s discretion.

ADVANCEMENT: MIDWINTER KING

There are two ways to advance to the final round of four combatants – by Victory or by Accolade.

Victory

The winners of each of the three tournaments automatically advance to the Midwinter King round.

Accolade

The list will be “balanced” by adding a fourth combatant chosen by the other combatants. If the list is already balanced, the Advancement by Acclaim will not be needed.

Once the four finalists are assembled, they shall fight with the prior scoring conventions in a simple single elimination tree. Fighters will be paired randomly.

APPENDIX A: SAFETY REQUIREMENTS

WEAPONS

All weapons will be tempered steel, flexible in the thrust, in good repair and free of burs or rust. A list of acceptable and prohibited weapons follow, along with reasons why a weapon is not permitted. Any weapons produced by an “unknown manufacturer” (see list) will be evaluated by the judges.

Swords with a rounded point the width of a quarter or built in button/nail do not need a blunt, otherwise they should have a standard rubber blunt of equivalent. Steel daggers must have a secured blunt; the Cold Steel rondel trainer is the preferred weapon for the tournament.

Acceptable Weapons/Manufacturers

- Albion Arms — All Maestro Line weapons other than the messer;

- Alchem — “Fiore” longsword;

- Arms & Armor — Fechterspiel, Spada da Zogho, Scholar Sword, Messer;

- Blackhorse Blades

- CAS IBERIA — Practical Bastard Sword, Flexi-blade rondel dagger

- Cold Steel – Rondel dagger trainer

- Danelli Arms — All basic and custom models;

- Darkwood Armory — All rapiers, daggers, sideswords and messers; older Scrimator and Fechtbuch longswords;

- Ensifer — Heavy Feder, Messer

- Malleus Martialis

- Pavel Moc — Feders and blunt longswords/messers permitted.

- Regenyei — Feders and blunt longswords/messers permitted.

Banned Weapons

- CAS Hanwei Feder (too flexible and prone to breaking)

- Ensifer Light (too light, too flexible)

- CAS Hanwei Tinker Longsword (too narrow an edge for safety)

“I don’t see XYZ sword…”

As noted, bring it and we’ll have a look. However, keep the following in mind:

- Minimum weight: 1450 g (longsword), 1000 g (one-handed sword);

- Maximum length: 130 cm

- Edge-width: 1.5mm

- Overly-flexible weapons are just as likely to be refused as overly-stiff ones.

ARMOUR

Head

Head protection must cover the entire head and front of the throat. There should be no gaps in coverage that would allow a thrust or strike to the face. A 3-Weapon Mask with SPES-style overlay or Absolute Force HEMA mask with back of head protection, should be considered minimally acceptable protection.

Throat

A covering to protect the throat. A solid, vs. foam gorget is strongly recommended, as is

Torso

Clothing should be puncture resistant, or three layers and completely cover the torso and arms completely. Padded jackets are strongly recommended for longsword fencing. Rigid chest protection, such as a modern fencing chest guard, is strongly recommended for female fencers.

Groin

A hard cup for all male combatants, which must not be visible while fencing. (Honestly, no one wants to see your cup and jock strap.)

Elbow and Forearm

Hard plastic, leather or steel elbow protection that protects the back and sides of the joint. Forearms should be protected by additional heavy padding, plastic, leather, etc.

Hands

Sturdy gloves or gauntlets must be used to protect the hands and wrists. Gloves must include protection on the sides and tips of the fingers sufficient to resist hard strikes from steel. An unsupplemented lacrosse glove is not sufficient. Most HEMA-dedicated synthetic gloves or gauntlets, such as Sparring Gloves and Black Lance or steel gauntlets are acceptable.

Feet

Shoes must be worn.

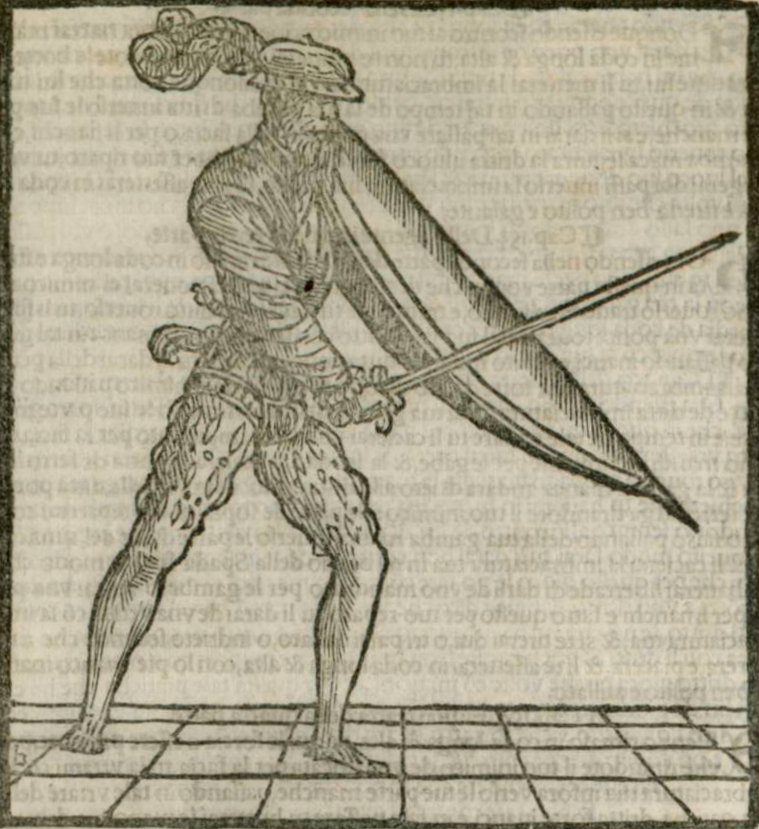

Usually, the imbracciatura is depicted as either kite or oval shaped, however, by the middle of the 15th-century, rectangular and “coffin” shaped shields also appear in artwork. As this is well into the Humanist era, with its interest in classical themes, the appearance, at least of the rectangular shield, may have been a way to reference the Roman scutum, much like the cinquedaea evoked the gladius and pugio or the interest in dueling with rotella and partisan called up the memories of heroic Greece.

Usually, the imbracciatura is depicted as either kite or oval shaped, however, by the middle of the 15th-century, rectangular and “coffin” shaped shields also appear in artwork. As this is well into the Humanist era, with its interest in classical themes, the appearance, at least of the rectangular shield, may have been a way to reference the Roman scutum, much like the cinquedaea evoked the gladius and pugio or the interest in dueling with rotella and partisan called up the memories of heroic Greece.

Cut the canvas to the edge of the shield using a box cutter. Place the leather straps on the back side and mark their placement. The top strap should be just below the armpit while the small strap should be an arm’s length away so the hand can grasp it.

Cut the canvas to the edge of the shield using a box cutter. Place the leather straps on the back side and mark their placement. The top strap should be just below the armpit while the small strap should be an arm’s length away so the hand can grasp it.