The Chicago Swordplay Guild (CSG) provides organized instruction in the serious study and practice of historical European swordplay.

Founded in 1999, the Guild is a modern school of swordsmanship and martial arts. We seek to be consistent with the methodology of the ancient European fencing schools by combining scholarship and research into the teachings of the historical Masters with the practical knowledge gained through solo and partnered drilling and fencing.

Since techniques are taught in reference to how effective they would be in a real encounter, the Guild practices with an absolute emphasis on safety, control, competence, and skill at arms.

What are Western Martial Arts (WMA) and Historical European Swordsmanship (HES)?

The rich tradition of European armed and unarmed martial arts is documented back to the 13th century. While some of these arts have survived to this day, many were discarded over the centuries as new weapons and methods of combat rose to take their place. Western Martial Arts (WMA) refers to the overall family of arts, while Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) or Historical European Swordsmanship (HES) refers to those branches of the WMA family that focus upon traditional weapons and may or may not be reconstructions of systems with no living lineage.

Fortunately, from the year 1300 generation after generation of Italian, English, French, German, and Spanish Masters at Arms recorded their methods in pictures and words. These treatises instruct students in unarmed combat, knife fighting and defense, swordplay, the use of polearms, and mounted combat. Currently dozens of these texts are undergoing translation and interpretation by a growing world-wide community of enthusiasts, martial artists, and scholars. The Chicago Swordplay Guild is proud to be part of the re-discovery and reconstruction of an effective and battle-tested Western martial arts tradition.

The “Martial Arts” are literally, the “Arts of Mars”, the Roman god of war, so it should be no surprise that Europe boasts a complex martial culture that extends back into antiquity and continues to this day. The Chicago Swordplay Guild connects with this tradition of Western martial arts by training in the historical fighting arts of Medieval and Renaissance Italy (1350 – 1650):

- The medieval “art of arms”, or armizare,of the dei Liberi Tradition

- The Bolognese swordsmanship of the early Renaissance

- The rapier: the premier dueling weapon of the high Renaissance

By the late Middle Ages, the Italian peninsula had become an ever-changing patchwork of petty kingdoms and free cities. There was no slow rebirth of town culture in northern Italy, because it had never truly perished. Instead the towns slowly re-established their dominance over the countryside and the urban nobility gained preeminence over their rural, land-holding brethren, led by a combination of military and administrative post, the “captain of the people” was often chosen from members of the old aristocracy, wealthy merchants, or from common-born mercenary captains. At first controlled by the dominant political party, the capitani grew increasingly powerful, and quickly became despots. In many cases, they dispensed with the new title and assumed the old hereditary titles of marquis, count or duke, whether they came from old noble families or were upstarts raising themselves up as the new nobility. Their wars to gain, hold, and influence other cities put the peninsula in a state of nearly continuous, small-scale warfare.

By the late Middle Ages, the Italian peninsula had become an ever-changing patchwork of petty kingdoms and free cities. There was no slow rebirth of town culture in northern Italy, because it had never truly perished. Instead the towns slowly re-established their dominance over the countryside and the urban nobility gained preeminence over their rural, land-holding brethren, led by a combination of military and administrative post, the “captain of the people” was often chosen from members of the old aristocracy, wealthy merchants, or from common-born mercenary captains. At first controlled by the dominant political party, the capitani grew increasingly powerful, and quickly became despots. In many cases, they dispensed with the new title and assumed the old hereditary titles of marquis, count or duke, whether they came from old noble families or were upstarts raising themselves up as the new nobility. Their wars to gain, hold, and influence other cities put the peninsula in a state of nearly continuous, small-scale warfare.

Desiring to establish their legitimacy, the despots sought to make their courts the envy of Europe. Those who embraced the new ideals of humanism became great patrons of art, science and learning. The lord acquired renown as a man of culture, learning and wealth, periodically gaining additional civil or military service from the courtier, while the courtier gained far more: stable financial support, prestige, and a chance to develop his work without having to fight against the pressure of daily life. It is a perfect summation of the late medieval Italian condition that the flourishing of ideas and artistic expression that became the Renaissance was built upon the bloody ambition of despotism.

All of these changes produced a culture in which members of a wide variety of social strata not only desired or required training in arms, but also had the means to acquire it. The professional fencing master or “master-at-arms” entered to fill the gap. Originating as a battlefield art, the practitioner had to be versed in a multitude of weapons including the sword, spear, and axe, in or out of armour, on foot or horseback, and against any number of opponents. As the Renaissance brought sweeping changes to European culture, so to did the Italian fencing traditions evolve and diverge, with a new focus on civilian swordplay. Eventually, a new, uniquely Italian weapon and fencing style —that of the elegant rapier— emerged and swept across Europe, influencing most of the continent for well over a century, and laying the theory of Italian fencing for the next three centuries.

The “Martial Arts” are literally, the “Arts of Mars”, the Roman god of war. It should be no surprise that Europe boasts a complex martial culture that extends back into antiquity and continues to this day. The Chicago Swordplay Guild connects with this tradition of Western martial arts by focusing on the historical fighting arts of Medieval and Renaissance Italy (1350 – 1650).

The CSG’s medieval martial arts curriculum is primarily based upon the surviving records of the tradition founded by the Friulian master at arms, Fiore dei Liberi. Dei Liberi gave no formal name to his school or his martial art, simply calling it armizare (the art of arms), and we only know that the style outlived the founder because of the surviving manuscript of another master at arms, separated from dei Liberi by two to three generations of time. While we know of this later master, Filippo Vadi, through the treatise he penned, dei Liberi’s fame was such that he has been the subject of periodic biographies over the last six hundred years, and the city hall of his hometown is to this day found on the Via de Fiore dei Liberi. Yet between them, these two men have left us a complete martial art of a richness and complexity to stand beside any other in the world.

The CSG’s medieval martial arts curriculum is primarily based upon the surviving records of the tradition founded by the Friulian master at arms, Fiore dei Liberi. Dei Liberi gave no formal name to his school or his martial art, simply calling it armizare (the art of arms), and we only know that the style outlived the founder because of the surviving manuscript of another master at arms, separated from dei Liberi by two to three generations of time. While we know of this later master, Filippo Vadi, through the treatise he penned, dei Liberi’s fame was such that he has been the subject of periodic biographies over the last six hundred years, and the city hall of his hometown is to this day found on the Via de Fiore dei Liberi. Yet between them, these two men have left us a complete martial art of a richness and complexity to stand beside any other in the world.

The Flower of Battle

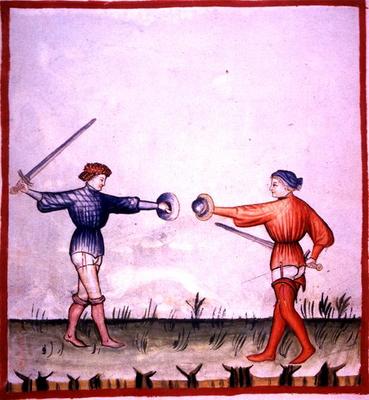

Fiore dei Liberi’s art is preserved in the manuscripts he left behind, all entitled il Fior di Battaglia (the Flower of Battle). Presented to the Marquise d’Este in 1409, at least five distinct copies once existed. Only four are know to survive, each with slight differences. The manuscripts are named for the collections that hold them: the John Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Pierpoint-Morgan in New York City, the Bibliteque National in Paris, and the Pissani-Dossi collection, formerly in Italy.

The Getty and Morgan manuscripts consist of illustrations accompanied by short paragraphs of text, while the Pissani-Dossi and BN copies replaces the paragraphs with rhyming couplets, perhaps meant as memory aids for the student. The Getty manuscript is the largest and most detailed of the three texts, presenting a carefully organized learning scheme. In the prologue dei Liberi provides his biography and credentials, including his five duels with other masters and the names and ranks of his famous students and their martial accomplishments. He then presents his basic tactical advice to the combatant, including priorities and cautions, followed by the requirements for fighting in hand-to-hand combat. The prologue ends with an explanation of the manuscript’s organization, and a dedication to Niccolò d’Este, Marquise of Ferrara.

The Getty and Morgan manuscripts consist of illustrations accompanied by short paragraphs of text, while the Pissani-Dossi and BN copies replaces the paragraphs with rhyming couplets, perhaps meant as memory aids for the student. The Getty manuscript is the largest and most detailed of the three texts, presenting a carefully organized learning scheme. In the prologue dei Liberi provides his biography and credentials, including his five duels with other masters and the names and ranks of his famous students and their martial accomplishments. He then presents his basic tactical advice to the combatant, including priorities and cautions, followed by the requirements for fighting in hand-to-hand combat. The prologue ends with an explanation of the manuscript’s organization, and a dedication to Niccolò d’Este, Marquise of Ferrara.

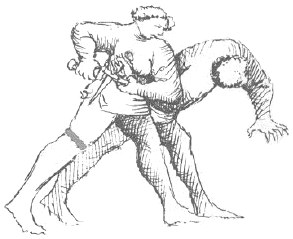

The Fior di Battaglia divides l’arte dell armizare into three principle sections: close quarter combat, long weapon combat and mounted combat. The close quarter combat forms the basis for many of the grappling and disarming techniques used in later sections of the manuscript, and is used in or out of armour, with the dagger section forming the single largest collection of techniques:

|

|

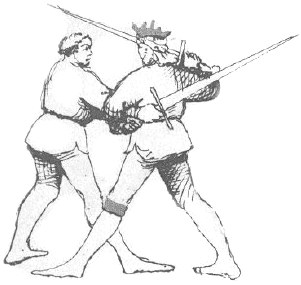

Long weapon combat begins with the introduction of the sword and swordplay forms the basis for all other long weapon combat. The treatise also includes several other “knightly” weapons used on foot, both in and out of armour, such as the spear and poleax. There are also several unusual weapons, such as monstrous, specialized swords for judicial combat, and hollow-headed polehammers, meant to be filled with an acidic powder to blind the opponent!

|

|

Finally, mounted combat, reintroduces many of the disciplines already presented, this time adapted for combat on horseback, again in or out of armour. While the Guild does not practice mounted combat, the mounted techniques contain many interesting insights into the other sections of the art of arms.

|

|

Within these subsections, dei Liberi taught his art through a series of zoghi (“plays”) —formal, two-man drills akin to the kata of classical Japanese martial arts— that were both technique and tactical lesson.

Filippo Vadi’s work, De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi, written c.1482, is very similar to the Pissani-Dossi manuscript, consisting primarily of beautifully painted figures with rhyming couplets. Vadi covers a smaller subset of weapons from Fiore: the dagger, the two-handed sword in and out of armour, the spear and poleaxe. The armoured combat techniques are reduced in scope, and abrazare, one-handed sword and mounted combat techniques are omitted entirely. But De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi’s unique virtue is its prologue of sixteen verse chapters, in which Vadi addresses the general and specific principles of swordmanship, such as the proper length of the sword, tactical advice for facing stronger opponents and multiple opponents, how and when to parry and to control the fight when the swords are crossed, and lessons on timing, feints and a few specialized blows. These chapters provide fascinating insights into the tactical application of the art, and add clarity and subtlety to many of the plays found in all four texts.

Filippo Vadi’s work, De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi, written c.1482, is very similar to the Pissani-Dossi manuscript, consisting primarily of beautifully painted figures with rhyming couplets. Vadi covers a smaller subset of weapons from Fiore: the dagger, the two-handed sword in and out of armour, the spear and poleaxe. The armoured combat techniques are reduced in scope, and abrazare, one-handed sword and mounted combat techniques are omitted entirely. But De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi’s unique virtue is its prologue of sixteen verse chapters, in which Vadi addresses the general and specific principles of swordmanship, such as the proper length of the sword, tactical advice for facing stronger opponents and multiple opponents, how and when to parry and to control the fight when the swords are crossed, and lessons on timing, feints and a few specialized blows. These chapters provide fascinating insights into the tactical application of the art, and add clarity and subtlety to many of the plays found in all four texts.

Armizare within the Guild

Armizare within the Guild

The dei Liberi tradition is the centerpiece of the CSG curriculum. It is the source for all of the abrazare, dagger and longsword material in the Guild’s novice curriculum, and this material is also expanded upon in the higher grades, with the introduction of the arming sword, armoured and polearm material.

Suggestions for Further Reading

- Biographies of Fiore dei Liberi and Flippo Vadi.

- CSG co-founder Gregory Mele and Luca Porzio’s English translation and analysis of Vadi’s De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi is available from Amazon.

- PDFs of the Novati facsimile of the Pissani-Dossi manuscript are available from the CSG.

- The Exiles have provided partial translations of all three dei Liberi manuscripts on their site, along with several video clips.

- Partial translations of the Getty and Morgan manuscripts can also be found on the Schola Gladiatoria webpage.

- Italian readers can find transcriptions of dei Liberi and Vadi’s manuscripts on the Sala d’Arme Achille Marozzo website.

- Nova Scrimia has a new English language video on the longsword, based upon the dei Liberi tradition, as well as an Italian companion book, La Nobile Arte della Spada (“The Noble Art of the Sword”)